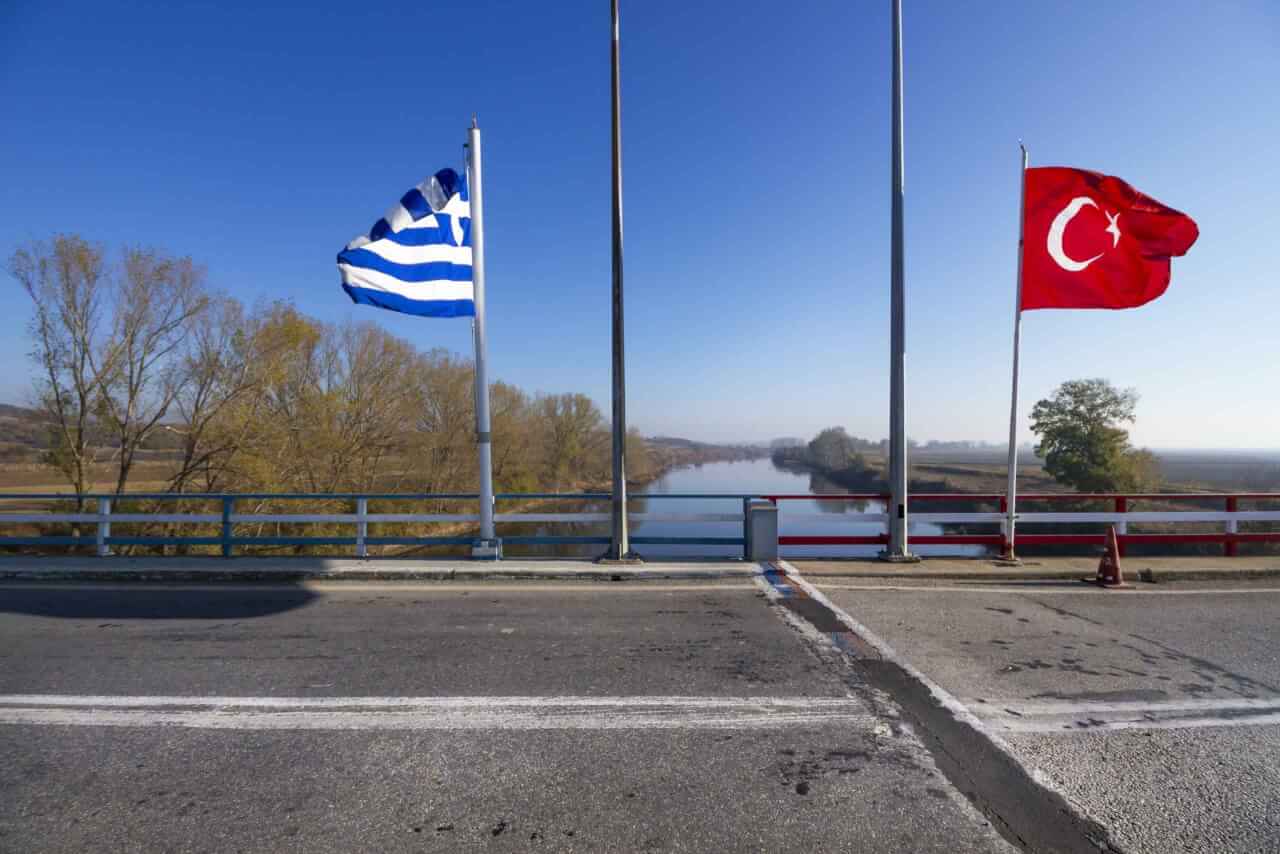

The deep-blue waters of the Aegean are often perceived as a dividing line between two peoples. In reality, for millennia, they have connected cultures, commerce, and daily life.

Today, the “islands question” between Türkiye and Greece is not merely a matter of diplomacy and international law; it also reflects the historical traumas deeply ingrained in the collective memories of both societies.

During my ten-day visit to Lipsi, Leros, and Patmos, I observed this reality firsthand through conversations with residents, mayors, politicians, and even military officers.

Historical Background

The islands, long under Ottoman sovereignty, changed hands amid the power struggles and wars of the early 20th century:

- 1912 Balkan Wars: The Greek navy seized Lesbos, Chios, Samos, and Lemnos.

- 1912 Italo-Turkish War: Italy captured Rhodes and the Dodecanese from the Ottomans.

- 1923 Treaty of Lausanne: Türkiye formally renounced its claims, recognizing Greek and Italian control.

- 1947 Paris Peace Treaty: The Dodecanese were transferred from Italy to Greece.

Today, the islanders live as Greek citizens. From a legal standpoint, Türkiye no longer has sovereignty claims. Yet this does not mean Ankara’s security and navigational interests can be brushed aside.

Shadows of Trauma

On the Greek side, the memory of the “Asia Minor Catastrophe” of 1922 remains vivid. The trauma of hundreds of thousands of Greeks forced to flee Anatolia continues to be passed down through generations. On the Turkish side, the atrocities committed during the Greek occupation of Western Anatolia and the forced displacement of Turks from the islands and mainland during the population exchange remain equally alive in memory. Thus, nearly every family on both shores carries scars. These painful recollections are easily inflamed by politicians, keeping alive an exploitable wound.

Fears, Realities, and New Dynamics

In Greece, suspicions linger: “Does Türkiye intend to take the islands back? Why was the Aegean Army created? Could there be a sudden landing, as in Cyprus?”

In Türkiye, anxieties run just as deep: “Why is Greece militarizing the islands in violation of Lausanne? Backed by the West, is it seeking to close off the Aegean to Turkish ships?”

In truth, Ankara’s primary stance is to preserve the status quo. Türkiye’s aim is neither annexation nor aggression, but the maintenance of an order consistent with the Lausanne and Paris treaties. Ultra-nationalist rhetoric exists on both sides, but it remains marginal.

A critical point must be emphasized:

• Lausanne and Paris explicitly required the islands to remain demilitarized.

• Today, Greece has heavily armed many of them.

This gives Türkiye a strong legal argument. While the current arrangement seems to favor Greece, such violations place Ankara in a stronger diplomatic position. Neither the EU nor the US can alter this reality: Türkiye has repeatedly declared it will not compromise on its vital national interests.

Refugees and Economic Interdependence

The issue is not only one of security but also of humanity. On Leros alone, nearly 3,000 refugees who arrived via Türkiye now reside, placing a heavy economic and social strain on the island. The solution must be both humanitarian and pragmatic. Türkiye itself hosts millions of refugees. A joint Türkiye–EU–Greece refugee management mechanism is no longer optional—it is essential.

Meanwhile, tens of thousands of Turkish citizens have purchased property in Greece through the “golden visa” program. For them, this is not only a gateway to EU free movement but also a way of channeling Turkish capital into tourism, construction, food, and shipping. This new class of cross-border property owners forms an invisible yet powerful economic and social bridge.

Reciprocity is key: just as Turkish capital flows into the islands, programs could also encourage a stronger Greek presence in Istanbul and along the Turkish Aegean coast. Thus, resolving Aegean disputes requires activating not only security channels but also financial, commercial, and cultural linkages. EU funds and joint investment mechanisms could serve as valuable levers.

Can NATO Provide a Framework?

This dispute could indeed be managed within NATO, of which both countries are members. I witnessed this firsthand. In my first posting at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, I worked frequently with NATO’s SHAPE headquarters in Mons to resolve the long-standing mutual vetoes between Ankara and Athens. For years, each blocked the other’s military investments and planning.

The lesson was clear: if a joint security mechanism is established, concerns about militarization can be managed under NATO oversight—provided there is a credible and honest broker. But if Athens insists on expanding its territorial waters to 12 miles and pressing excessive EEZ claims, this would indeed constitute a casus belli. This is no exaggeration. Such steps would effectively blockade Türkiye’s access to the Aegean and Mediterranean.

Signs of Hope

Even in the shadow of historical wounds, hope persists.

Last year alone, 1.4 million Turkish tourists visited the Greek islands, serving as a vital lifeline for local economies. Shared tables of ouzo and rakı, young Turks and Greeks dancing side by side—these are not just leisure moments but glimpses of a better future.

A Roadmap for Constructive Solutions

Breaking the deadlock requires not confrontation, but diplomacy and confidence-building:

- Reaffirm Demilitarization: Under NATO or UN supervision, implement transparent monitoring of the islands’ non-military status.

- Joint Security Mechanism: Greece guarantees that the islands pose no threat; Türkiye, in return, renounces revisionist aims.

- Cooperation in Economy, Energy, and Migration: Share the refugee burden fairly between Türkiye, Greece, and the EU. Develop joint ventures in tourism, renewable energy, and fisheries. Leverage Turkish capital in Greece and EU funds as tools of mutual confidence.

- Cultural Bridges: Launch shared heritage projects, festivals, and youth exchanges to build societal trust.

The Path Forward

Türkiye and Greece remain caught in the shadows of history and mutual suspicion. Yet the Aegean islands need not be a perpetual flashpoint. Managed wisely, they could become bridges of cooperation and security.

Türkiye’s priority should be to defend its rights under international law, challenge violations of the status quo, and take necessary deterrent measures—while simultaneously pursuing constructive neighborly relations.

If Greece, too, can resist its extremist voices and adopt a similar approach, a new era of diplomacy and people-to-people engagement can begin.

The choice is whether to see the glass half-empty or half-full. For the sake of both nations—and the wider region—it is time, in my view, to focus on the latter.