Abstract*

Before the foundation of the modern republic in Turkey, the Ottomans did not regard the Tigris and Euphrates as two separate waterways. Snowmelt during spring seasons and rainfall flowing from the Taurus and Zagros Mountains allowed the growth of livestock, grains and crops over the banks of the twin river until pouring into the Shatt Al-Arab in Basra (Husain, 2021). With the emergence of the modern nation-state system in the Middle East, the management and utilization of waters in the Tigris and Euphrates underwent a fundamental transformation. The two river systems were divided among the newly established states of Turkey, Syria, and Iraq. Specifically, 33% of the Euphrates River basin and its tributaries lie within Turkey, 19% in Syria, and 46% in Iraq. As for the Tigris River basin, 15% falls within Turkey, 0.3% in Syria, 75% in Iraq, and 9.5% in Iran (Maden, 2012). Iraq and Turkey never reached a conclusive agreement on the allocation of water of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers since their independence.

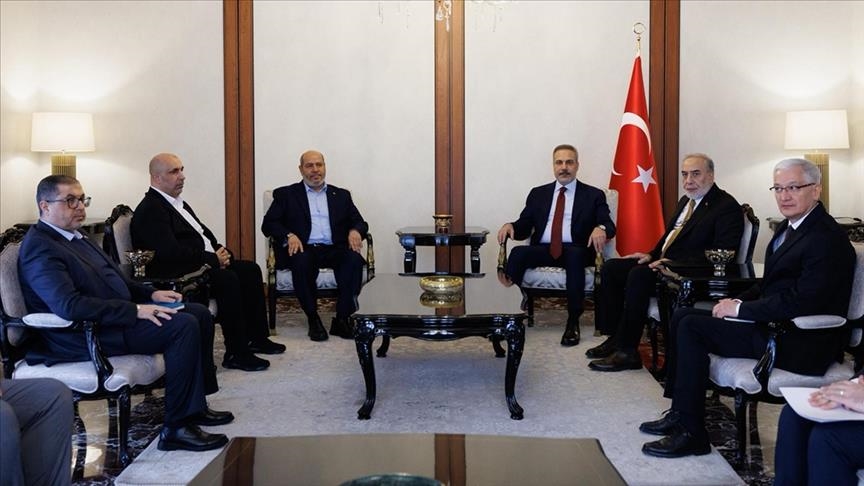

In recent years, the water negotiations between the two countries gained a new momentum as Turkey and Iraq began exploring a new trajectory of cooperation in joint Water projects. This policy brief firstly explains the legal positions of Iraq and Turkey with regard to the allocation of water in Tigris and Euphrates, and how bilateral political relations impacted their water talks. Secondly, the policy brief evaluates the contemporary context and the main dynamics behind the water cooperation projects between Turkey and Iraq. Finally, the paper draws attention to the main internal challenges in Iraq against the resolution of the water problem between Turkey and Iraq.

Unsuccessful Negotiations and Delayed Agreement on The Allocation of Water

Turkey and Iraq adopt different legal arguments on the allocation of the Tigris and Euphrates water. Iraqis argue that the Tigris and Euphrates have given life to the inhabitants of Mesopotamia for thousands of years, and that it has established irrigation installations, including the ancestral irrigation systems left from the Sumerians times, to irrigate these lands (Korkutan, 2001, p.21). Put differently, Iraqis argue that their share in water ought to be protected as an “acquired right”, and that no upstream country is entitled to take away the rights of these inhabitants. On the other side, Turkey argues that depleting water resources of a unitary basin system “is not a useful approach” because one cannot share a commodity which is constantly changing in quantity and quality in time and space under variable conditions (Ibid). Turkey did not sign the UN Watercourses Convention in 1997, which gives each riparian state an equal status and an equitable share of the waters of transboundary rivers. Instead, Turkey prefers negotiating the water issues with Syria and Iraq on a bilateral level (Kibaroğlu, 2022, pp82-83).

There is no conclusive agreement on the amount of water to be released from the Turkish borders since the Turkey-Iraq Treaty of Friendship and Good Neighbourly Relations was signed by Turkey and Iraq in 1946. The treaty included a protocol on the regulation of Tigris and Euphrates flows, emphasizing flood control and joint planning for storage facilities in Turkish territory. Yet the technical negotiations on allocating water resources in the Tigris and Euphrates, which started in 1960s between Turkey, Iraq and Syria, did not yield concrete outcomes. The dynamics of the political relations between Turkey, Syria and Iraq were intertwined with their relations as upstream-downstream countries in the Euphrates and Tigris basin, exactly when the new round of negotiations started.

It is important to highlight a set of several external events that led Iraq to endorse a track of cooperation with Turkey on water. Iraq lagged behind Turkey in developing its water infrastructure following the UN sanctions imposed on Iraq in the 1990s. Iraq lacked the ability to finance and upgrade its infrastructure in order to manage its water resources in the Tigris and Euphrates. After the U.S. invasion in 2003, dams, pumping stations, canals, seawater desalination plants, and wastewater treatment plants were damaged by the US bombings. Turkey and Iraq capitalized on the momentum of developing their political relations in 2008 to restart their technical negotiations on water. Iraq positively responded to Turkey’s initiative for water cooperation with downstream countries under the rule of the AKP government which dismisses the idea that dams are a reason for interstate conflicts. Turkey, Iraq and Syria agreed to establish a Water Institute to institutionalize their trilateral technical negotiations on water allocation in 2008 (Dohrmann & Hatem, 2014, pp.567-583).

Bilateral Cooperation and Joint Water Projects between Turkey and Iraq

Under the domestic pressure of its poor water governance strategy, electricity cuts and shortage of drinking water, the consequent Iraqi governments saw a solution in cooperating with Turkey to solve their problems. Iraq signed bilateral agreements with Turkey in 2009 and 2014 to cooperate on water development, drought management and environmental protection, flood protection and water efficiency (Kibaroğlu, 2022, p.84). In 2017, Turkey and Iraq formed five working groups “to address various aspects of the water issue, including the prospect of joint dams at the border, water quality, desertification, dust and sand storms, measurement methods and water management training.” (Shapland, 2023, p.36) Turkey positively responded to the Iraqi requests to delay the filling process of the Ilısu dam during severe drought times in 2018, and agreed on the filling methods that allowed adequate water supplies to Iraq. In 2019, Turkey appointed its ex-head of State Hydraulic Works (Devlet Su İşleri – DSİ), Veysel Eroglu, as a special envoy to boost water cooperation with Iraq. In the ‘10-Year Water Management Agreement’ signed between Iraq and Turkey in 2024, both sides agreed to establish a joint fund to build joint dams and launch land reclamation projects.

The poor status of Iraq’s water infrastructure can be obviously observed in the case of Basra city, where the water of Tigris and Euphrates flows into the Shatt-Al Arab. Basra, inhabited by 3.5 million people, has been suffering a water shortage crisis owing to many factors, including high temperature, intrusion of saltwater from the gulf as a result to the drying up of Euphrates and the reduced Tigris flow. In Summer 2018, more than 118,000 people were admitted to the hospital with signs of contamination after drinking tainted water in Basra. As a result of such ongoing problems, recently. Basra’s governor paid a visit to Turkey in August 2025 to secure further Turkish investments in water projects and agriculture. He signed a twinning initiative with Istanbul to replicate Istanbul’s water distribution and transport projects in Basra.

The chances of cooperation on water between the two countries look high since both of them agree on the concept of using water as an abundant source for economic growth. Turkey and Iraq adopted the practice of building dams in their national strategy for managing their water resources in the Tigris and Euphrates since the 1980s for electricity production purposes and massive irrigation plans. Following the ‘10-Year Water Management Agreement’ signed in 2024, the Iraqi Ministry of Water Resources prepared investment proposals for Turkish companies to build the Abu Takiya dam in Sinjar/North Iraq, the Abyad 2.0 Dam in Karbala and Al-Kharaz Dam in Samawah Governorate.

Turkey’s renewed peace talks with the PKK in 2025 to lay down their weapons and dissolve themselves is a positive development that encourages Ankara and Baghdad to explore new opportunities for cooperation in water issues. For example, Turkish President Erdogan agreed to the request of Iraq’s Head of Parliament to release 420 cubic m3/second of water to curb the problem of water shortage and drought during the summer of 2025. The renewed talks with the PKK came at a time when Turkey began to institutionalize its economic ties with Iraq. In April 2025, a delegation of Turkish officials conducted site visits to Sinjar/North Iraq in order to examine the technical details of the Abu Takiya Dam Project.

Internal Critics and Challenges Against the Iraqi Government and Turkey

Despite promising prospects of cooperation on water between Turkey and Iraq, and ongoing collaborative efforts, Turkey’s initiatives to help Iraq to address its water problems continue to face persistent and complex challenges. In July 2023, Iraqi protestors demonstrated against frequent power outages and shortages of drinking water, largely attributed to high levels of corruption in the local levels of the Iraqi government, and also directed their anger toward Türkiye. Gathered near the Turkish embassy in Baghdad, they also accused the Turkish government of reducing the flow of rivers into Iraq. In response to such accusations, Türkiye has been denying that the dams built on the watercourse of the Euphrates and Tigris are the reason behind Iraq’s water scarcity problem. Instead, Türkiye has been arguing that the waste of water in Iraq, caused by the mismanagement of water resources and the damaged water infrastructure (dams and channels), is the reason behind Iraq’s water and electricity problems. However, this does not prevent the water issue from becoming an important issue in Iraqi domestic politics.

The Iraqi government is frequently criticized in the parliament for not reaching an agreement with Türkiye on a precise share for Iraq in the water of the Tigris. Iraq fears that it will suffer from the unintended consequences of the filling process of the Turkish dams as long as there is no binding agreement on sharing water with Türkiye. Critics are blaming Iraqi government officials for not using Iraq’s economic leverage as an oil-producing country against Türkiye to negotiate Iraq’s share of water.

At the same time, the future of Türkiye’s military presence in northern Iraq makes it hard for the Iraqi government to conclude a final agreement on water with Ankara. Critics argue that launching joint projects with Türkiye in water risks opening the door to increasing Türkiye’s geopolitical leverage. Critics fear that the Turkish military presence in disputed northern territories could be sustained for other purpose, mainly those related to defending the prospective Turkish dam projects and Turkish personnel.

The disparity between Türkiye and Iraq in terms of institutional capacity and damming facilities raises fears among Iraqi experts that Iraq does not have a leverage in the water talks with Türkiye. In that regard, Iraqi environmentalists advocate against the Turkish dams and irrigation projects, which are blamed for the further shrunk of Iraq’s marshlands, added to UN World Heritage List in 2016, and the scarcity problem of water in Iraq’s southern cities, mainly Basra. Iraqi water experts fear that, under the current conditions, Iraq risks accepting storing its water resources in the reservoirs built over Turkish territories. This issue raises the alarm that Iraq might fall under the risk of importing hydroelectric power generated by the Turkish dams to solve its chronic problem of power outage and electricity blackout.

Conclusion

The prospects of water cooperation between Türkiye and Iraq in the future remain vague despite of the promising opportunities offered by their joint water projects. The Iraqi government might remain under internal pressure from critics within the parliament and the ordinary Iraqis for its failure to solve the problems of electricity cuts and drinking water shortage. Iraqi officials are benefiting from the joint water projects to increase the credibility of their water governance strategy. Despite that, the Iraqi government will stay in a weak position against its critics as long as it does not reach a conclusive agreement with Türkiye on the allocation of water in the Euphrates and Tigris.

The dynamics of Türkiye’s military activities against the PKK in northern Iraq remain a key factor shaping its water negotiations with Iraq. Türkiye’s water projects in Iraq are likely to serve as a cornerstone of any future comprehensive water agreement between the two countries. Any prospective deal-making process will have to account for the security of these projects and the safety of Turkish personnel in Iraq. In assessing the prospects of a workable water-allocation agreement on the Tigris and Euphrates, policy makers and analysts will need to monitor key policy indicators, particularly border security and the state of PKK peace talks, as measures of progress toward a sustainable accord.

Bibliography

Ayşe Kibaroğlu, “Türkiye’s Water Security Policy: Energy, Agriculture, and Transboundary Issues”, Insight Turkey, Vol.24, No.2, 2022.

Faisal Husain, Rivers of the Sulan: The Tigris and The Euphrates In the Ottoman Empire, (New York: Oxford University Press, 2021).

Greg Shapland, Water Security in Iraq, LSE Research Online Documents on Economics (London School of Economics and Political Science, LSE Library, 1 May 2023).

Mark Dohrmann and Robert Hatem. “The Impact of Hydro-Politics on the Relations of Turkey, Iraq, and Syria.” Middle East Journal 68, no. 4 (2014): 567–83. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43698183, Retrieved at 10 August 2025.

Salih Korkutan, “The Sources of Conflict in the Euphrates-Tigris Basin and Its Strategic Consequences in the Middle East”, Master Thesis, U.S. Naval Postgraduate School, December 2001.

Tugba Evrim Maden, “Water Resources Management in Iraq”, ORSAM, ORSAM Report No.122, May 2012.

*This paper is part of a research project: “Turkey-Iraq Relations: Opportunities and Tensions in Security and Connectivity” is a project of CATS Network. The Centre for Applied Turkey Studies (CATS) at the Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik (SWP) in Berlin is funded by Stiftung Mercator and the Federal Foreign Office. CATS is the curator of the CATS Network, an international network of think tanks and research institutions working on Turkey. “Turkey-Iraq Relations: Opportunities and Tensions in Security and Connectivity” is a project of CATS Network.