Turkey’s Tough Balancing Act: Action Without Exposure?

The recent very intense escalation between Iran and Israel introduces a dangerous new variable into Turkey’s already dense foreign policy agenda and may trigger further turbulence in an agenda that is already stretched to its limits. While Ankara has long aimed to position itself as a regional balancer, this latest conflict may force a recalibration of its carefully maintained neutrality and strategic flexibility. Because Turkey is not solely focused on the Middle East. For example, On June 2, Turkey once again hosted Ukraine–Russia talks—this time after a long diplomatic lull during which it had been largely sidelined. The meeting, reportedly driven in part by U.S. pressure, came just one day after Ukraine escalated the war by extending its military operations onto Russian soil. While Turkey may lack the leverage to directly influence the outcome of the conflict, its ability to bring both sides together remains a commendable diplomatic feat. However, this development also raises two fundamental and uncomfortable questions. First, does Turkey truly possess the capacity—both politically and economically—to sustain such high-profile international engagements? The country is grappling with deep-rooted structural challenges, chief among them a protracted economic crisis. Second, and perhaps more critically, to what extent will Turkey’s ongoing authoritarian drift at home undermine its international credibility and flexibility? As domestic politics grow more hegemonic and centralized, projecting a balanced and effective foreign policy becomes increasingly complicated.

Turkey’s Heavy Agenda

In recent weeks, Turkey has experienced various level of political and diplomatic activity that could normally span several years in any other country’s agenda. For instance, On May 12, the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), which has been engaged in various political and militant actions within Turkey for over four decades, announced that it would lay down arms in response to a call from its imprisoned leader, Abdullah Öcalan. Just a week prior to this development, Turkey was mentioned during the Informal Meeting of EU Foreign Ministers held in Poland as a country that could play a pivotal role—both at the negotiation table and on the ground—in the Russia-Ukraine peace process.

Undoubtedly, these are highly complex and demanding issues. However, this might merely represent the visible portion of a much deeper and more complex set of underlying dynamics. Nevertheless, on May 20, Turkey participated—at the level of deputy foreign minister—in a trilateral summit with the United States and Syria held in Washington, engaging in discussions concerning the regulation of ISIS detention facilities. Simultaneously, Turkey is preparing to launch negotiations for a Free Trade Agreement with the United Kingdom during the summer and will also take part in the second round of Cyprus negotiations scheduled to be held in Geneva in July. In short, just as the past weeks have been marked by intense diplomatic activity, Turkey’s upcoming agenda is similarly packed, and likely to be shaped by a parallel diplomacy dynamic. This density of engagement, of course, stems from Turkey’s geographical location and geostrategic significance. Yet, the more critical question is whether Turkey possesses the institutional capacity to effectively manage and digest such a heavy and multidimensional agenda. The outcomes of these developments will not only affect Turkey but also carry significant implications for regional stability and the broader international order.

The issues of Syria and the PKK constitute an intertwined and deeply rooted entanglement

In late 2024, Devlet Bahçeli, leader of the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP) and long-time ally of President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, made a move few anticipated: he was seen publicly greeting pro-Kurdish DEM Party MPs and went on to suggest that Abdullah Öcalan—the jailed PKK leader—could one day be pardoned and even return to political life. This stunning statement ignited speculation that covert negotiations, led by Turkey’s National Intelligence Organization (MIT), had reached a critical juncture in efforts to disband the PKK.

Shortly after, another geopolitical earthquake followed: the sudden collapse of the Assad regime in Syria, replaced by a Turkish-aligned interim government led by Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS). While this regime change highlighted Ankara’s deepening entrenchment in northern Syria, it also intensified a volatile new dynamic—the empowerment of the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), a U.S.-backed coalition with strong PKK ties. Together, these developments reveal a bold recalibration of Ankara’s regional strategy: dissolving the PKK threat, reshaping Syria’s political future, and absorbing Kurdish actors into a Turkey-friendly framework. But that vision collides with domestic fragility. Soaring inflation, fiscal exhaustion, and rising social unrest are constraining Turkey’s ability to pursue such ambitions. Increasingly, Gulf states are steering the pace of diplomacy, often relegating Ankara to a reactive role.

If PKK talks collapse, the backlash may erupt first in northern Syria and quickly spill over into Turkish territory—jeopardizing existing gains for uncertain ends. The stakes are high, and the margins for error are thin. In this high-stakes game of regional reengineering, Turkey risks not just strategic overreach but also the unintended unravelling of its own carefully managed influence.

Engaging in the Russia-Ukraine Peace from the edge of the table

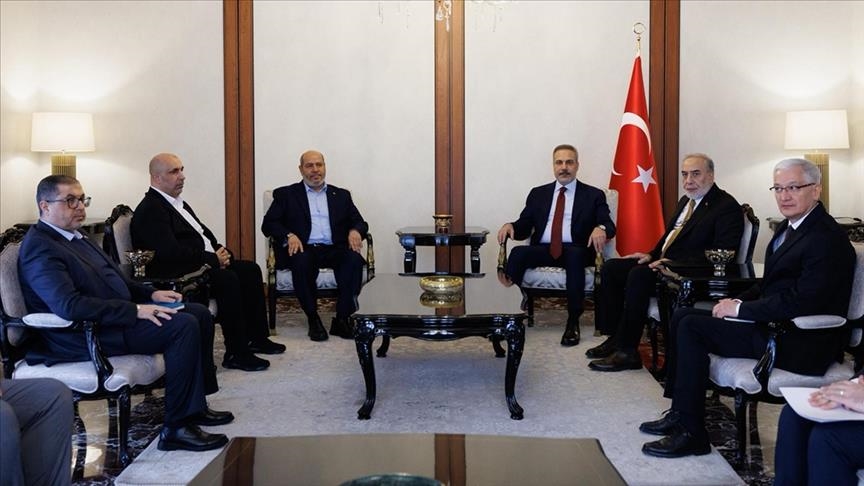

Since the outset of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Turkey has positioned itself as a key intermediary between the warring sides. It was the first country to host direct negotiations between Russian and Ukrainian delegations, and through the Grain Deal, Turkish diplomacy played a vital role in preventing a looming food crisis across Africa. By strictly enforcing its rights under the Montreux Convention and limiting access to the Turkish Straits, Ankara also helped prevent further military escalation in the Black Sea.

Throughout the war, President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has remained the only NATO leader in uninterrupted, direct dialogue with both Vladimir Putin and Volodymyr Zelenskyy—a posture rooted in pragmatic realism rather than idealist mediation. Most recently, Turkey achieved another diplomatic milestone as the table establisher for both fighting sides. Although this latest round of talks may ultimately remain symbolic, even Ankara had not anticipated its successful orchestration. Nonetheless, it confirms Turkey’s continuing relevance in any prospective peace settlement, especially regarding Black Sea security and the potential deployment of an international peacekeeping force—issues of substantial geopolitical and military consequence.

Yet a critical question remains: Does Turkey have the institutional strength and strategic leverage to transform its diplomatic efforts into lasting influence and tangible gains? There is potential for Ankara to contribute meaningfully to Ukraine’s postwar reconstruction—especially in areas like construction and logistics, where Turkish companies already hold a competitive edge. However, there is growing concern that Turkey could be marginalized in more lucrative, long-term sectors such as energy, digital infrastructure, and transportation—domains where Gulf states, Western Europe, and China may dominate the playing field.

If so, Turkey’s involvement could end up being limited to short-term wins, falling well short of the strategic and economic returns its weakened economy so urgently requires.

Between Brussels and London: Turkey’s diplomatic outreach and the limits of domestic governance

Turkey stands at a critical geopolitical juncture, seeking to leverage its strategic location and regional influence through an increasingly multifaceted foreign policy. In the coming months, Ankara is expected to modernize its Customs Union agreement with the European Union and reengage in talks aimed at resolving the Cyprus dispute.

Each of these tracks holds significant potential to enhance Turkey’s economic integration and geopolitical relevance in the Euro-Atlantic space. Simultaneously, Turkey’s defence industry has become an indispensable component of European security calculations. From drone technologies to regional military capacities, Turkey is positioning itself as a key actor in the evolving architecture of European defence. These developments offer Ankara substantial diplomatic capital—if coupled with strategic foresight and multidimensional diplomacy, they could yield long-term political and economic gains.

However, in recent months, Turkey’s domestic landscape has witnessed an alarming democratic regression. The politically charged arrest of Istanbul Mayor Ekrem İmamoğlu, the targeting of opposition-held municipalities, and an aggressive campaign to silence independent media point to a systematic effort to neutralize dissent. Even more troubling are the extra-legal maneuvers seemingly designed to push the main opposition party, CHP, out of the political arena altogether. These developments not only threaten pluralistic governance at home but also undermine the very credibility Ankara seeks to project abroad. While Turkish diplomats work to re-anchor the country in the Euro-Atlantic space, the government’s increasing reliance on authoritarian tactics sends the opposite message. It’s a contradictory balancing act: seeking long-term economic integration and regional prestige while hollowing out the institutions that would make such ambitions sustainable.

The question is no longer whether Turkey can play a larger role in global affairs—it clearly can. The real question is whether it can do so without first confronting the erosion of democratic norms at home. Without meaningful reform, Ankara risks forfeiting the strategic advantages it has worked so hard to gain. In a world where legitimacy and soft power matter as much as military hardware, Turkey cannot afford to keep burning both ends of the candle.

Strategic weight, fragile foundations

Despite Turkey’s rising international profile and assertive diplomatic engagement, the country finds itself in an increasingly paradoxical and fragile position on the global stage. Ankara has succeeded in making itself indispensable across multiple geopolitical theaters—ranging from NATO’s southeastern flank in Europe to complex conflict zones in the Middle East, and strategic corridors in Eurasia and the Caucasus. Whether through mediation in the Russia–Ukraine war, involvement in Libya and Syria, or balancing ties between Western and non-Western blocs, Turkey has cultivated the image of a pivotal power whose absence would destabilize multiple regions at once.

Yet beneath this hyperactive foreign policy lies a troubling domestic reality. Chronic economic turbulence, ongoing democratic erosion, and the deinstitutionalization of governance structures continue to hollow out the very foundations that sustainable global influence requires. Turkey’s foreign policy ambitions are expanding outward, but its domestic resilience is contracting inward—creating a dangerous asymmetry between projection and capacity. The country risks becoming a “necessary actor” in theory, yet one increasingly unable to consolidate or institutionalize its influence in practice.

Unless this internal fragility is urgently addressed through serious economic, legal, and political reforms, Turkey’s international assertiveness may remain performative rather than transformative—strong in visibility but weak in endurance. The real question is no longer whether Turkey matters, but whether it can matter in ways that are credible, consistent, and lasting.