Understandable is not necessarily acceptable. Now that the peace process to end the war in Ukraine seems more serious, the discourse and actions of the Russian elite are again under scrutiny. A brief historical overview may help to understand them, although one selectively gets from historical experience only what they want/need/instrumentalise. The current Russian elite seems obsessed with “the West”, apparently blinding them and blurring all.

In this respect, Eurasianism, which has become fashionable again in the post-Soviet era, was a substantial suggestion despite the abomination it has recently received in one way or another. Classical Eurasianism relied on the claim that Europe was not the only source of development and progress and on the observations that geography, history and social cohabitation in Eurasia have exposed a hybridity, thus a uniqueness. Accordingly, Eurasian development could not be in the “Western” way, although the ultimate aim is explicitly to reach that level (See Shlapentokh, Yanık, Mehlich, among others).

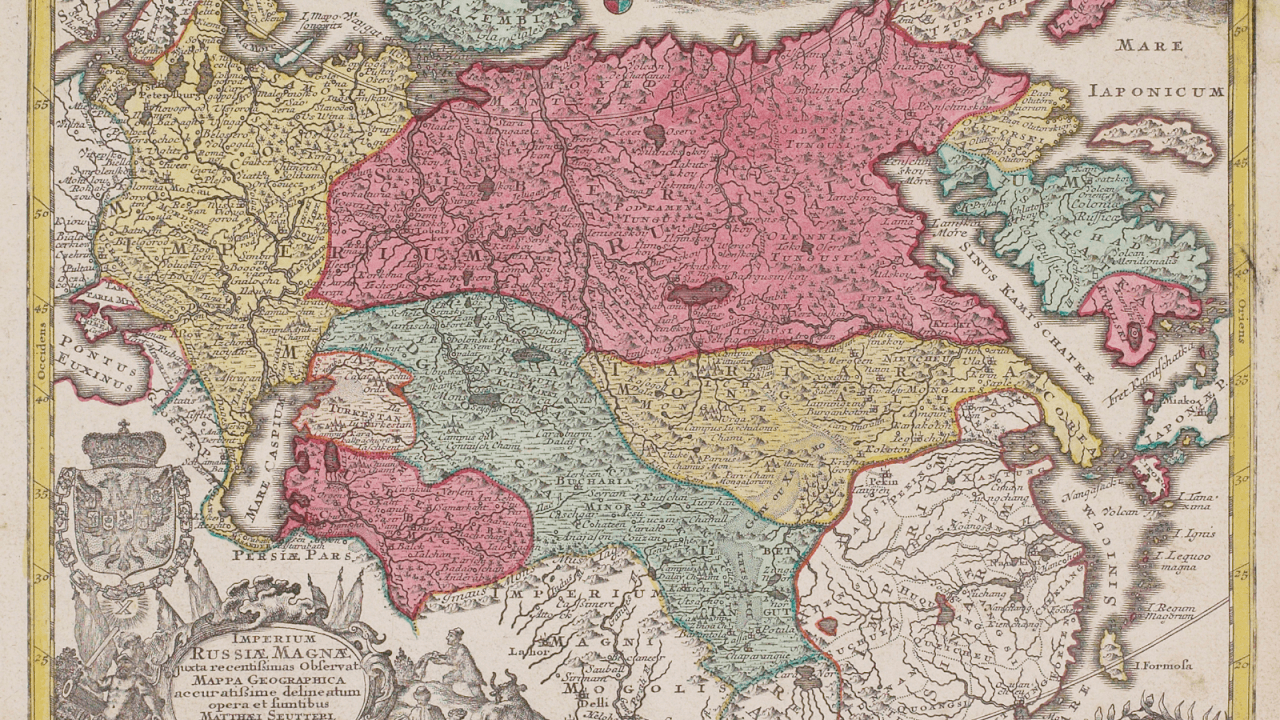

As a matter of fact, Eurasian history has not been detached from “the West” (to revisit this discussion on “the West” at the global level, see Hall). The beginning, indeed currently contested between Russian and Ukrainian nationalists, by Yaroslav the Wise, as the Grand Prince of Kiev from 1019 until his death in 1054, was marked by observation and even admiration of the (Eastern) Roman Empire as well as a Scandinavian alliance to weaken this influence, also because Swedish Kingdom desired to move south. (This relation of Kiev to “the West” in 11th century was and would not be the case for China or India, for example). As the leader of a kingdom from the Baltics to the Black Sea, whom was occasionally able to challenge Constantinople as in 1043, Yaroslav Vladimirovich was indeed wise enough to set an Eastern European state with stable political authority through administrative improvements such as a prototype parliament (Duma), unified society (through religion, language and culture), military security and organised economic activities (agriculture and raw materials, mostly to the European market, as usual since then).

The consolidation by Ivan the Terrible of the Muscovite Kingdom (reign: 1533-1584) was not much different in this sense. Ukraine began to be formed when ‘Rus’ moved north to Moscow, and the current war encouraged Ukrainian nationalists to call Russians as ‘Muscovites’. Ivan, who could be called ‘Great’ instead of ‘Terrible’ if he did not have a truly terrible personal life, was in regular contact with “the West”, such as German states, even with a demand for expertise or a trade agreement with England in 1555 Is it not striking that London and Moscow could communicate this much in the 1550s? However, it should be noted that by missing salient developments such as the Reformation and Renaissance, Russia was also an isolated world of its own.

Perhaps no need to mention Peter the Great or Catherine the Great (a native German speaker and French admirer) of the 17th and 18th centuries, while outlining that Russia was not detached from “the West”. Great reformers they were, to introduce rationalism, secularism, science, education and thereby institutionalisation, à l’européenne. The Russian aristocracy spoke French even in their daily life.

The colonialist discourse and practice of Russian rulers in their conquest of the Caucasus and North-eastern and Central Asia had rather been confirmation that they were “Western”. (Remember Dostoevsky: “In Europe we were Tatars, while in Asia we too are Europeans”). For instance, the Steppe Statute in 1891 resulted in a vast dispossession of land and genocidal loss of human life in Central Asia, encouraging even more resistance, most significantly by Kazakhs. (For a historical overview, see Riasanovsky and Steinberg)

The terrible Tsarist heritage could be managed only by a non-national modern state, as the Soviet Union was. Eurasianism was strengthened in fact by this demonstration that a modern state could be non-national and successful in delivering public order and service as well as obtaining international respect. It was not by coincidence that classical Eurasianists initially supported the Soviet Union: It revitalised their main arguments (though with Socialism that Russian nationalists would deem “a Western idea”): neither aristocracy nor democracy; uniformity of ruling elite around a ruling idea and loyalty of the masses; Empire or Federation, but no nation-state; people’s rights instead of individual rights; classless state (though not free enterprise as they favoured); continental interdependence (well proven by Soviet industrialisation policies); collectivity with an umbrella identity and culture (For example, Sovietskaya Cultura).

Finally, post-Soviet Russia, as a “bleeding hulk torn from the carcass of USSR” (as labelled in Service), received Liberalism as a destruction (See Popov) due to the tragically flawed direction by international actors and implementation by national actors (For an astute criticism, see Stiglitz). The economic liberal reforms were not done democratically at all, to the extent of bombardment of the democratically elected parliament by the army on the orders of a democratically elected president. The picture is clear, at least for Russians: Liberalism ruined lives and was imposed with the use of force. Add to these their -rather self-convinced yet crudely objective- argument that they have always been attacked from the west, from the Swedish Empire in medieval times to the (post) Cold War era. (Let’s also note that many European states were attacked, from the west). Thus formed the mindset of the current Russian elite. However intellectually implausible contemporary Eurasianism may seem because of its (self-)imprisonment in narrow political-military mentality and regime security, classical Eurasianism’s effort to provide a “non-Western modernisation” has been serious. It should be noted that this -flawed- label “non-Western modernisation” has been pretty “Western”. After all, in contemporary global polity, “The West” seems to be different forms of democratic capitalism, and “non-Western” different forms of authoritarianism, still within capitalism. All depends on the form and substance of democracy in its full definition of fundamental rights and freedoms.

Contemporary Eurasianism seems dramatically limited to the defence of this unnerving authoritarianism and state/regime security, from Ivan’s Oprichnina to Nikola’s Ohrana, to Soviet Cheka and KGB, to Putin’s National Guard. The rest is dubious at most: Russki Mir is not Sovietskaya Cultura because it is rather a form of political domination than an umbrella identity and culture; no classless state at all (See Lester, Salmenniemi and Ishchenko). No democracy and a new aristocracy as oligarchs over means of production; continental interdependence seems at most what Eurasian Economic Union can become because it currently is not; Russian Federation is a federation with people’s rights yet also looks like a Russian nation-state at its core; and finally, if there is a ruling idea, it seems bad old nationalism, which is quite “Western”. The Russian elite seems to think they can overcome all these shortcomings and failures with the use of force. It may be understandable yet not necessarily acceptable. War in Ukraine looks like the graveyard of contemporary Eurasianism in practice.

If any Eurasianism exists, it is currently being pursued by China through the Belt and Road Initiative, which aims to subordinate the whole of Eurasia to the Chinese political economy, and it has been successful so far. Russian elite does not seem aware of the fact that they facilitate this Chinese political economic domination, while claiming that they defend their -narrowly political-military- security. This also displays that a narrowly defined understanding of security actually challenges sovereignty.