For three decades after the Cold War, the Black Sea was treated as a secondary theatre: a transit basin for oil and grain, a buffer zone shaped more by legal regimes than by hard power, a space that mattered mostly to its littoral states. That mental map is now dangerously outdated. In 2026, the Black Sea has become one of the central fault lines of the emerging European and transatlantic security order – a place where energy, food, trade, military deterrence, cyber risk, maritime law and great-power rivalry intersect. What the war in Ukraine did was not to create the Black Sea’s importance, but to expose it. The basin has moved from being a quiet corridor to a contested strategic system. Ports, offshore gas platforms, subsea cables, tankers, grain ships, naval bases, insurance markets and diplomatic red lines are now all part of the same chessboard.

A Sea of Continental Scale

The Black Sea is not a small regional pond. The coastal and near-coastal countries together account for well over 300 million people if Russia is included, and roughly 170 million even when Russia is excluded. Their combined economic output is measured in trillions of euros. The European Union alone trades more than € 300 billion annually with Black Sea countries. This is a basin that connects Europe’s industrial heartland to the Caucasus, the Caspian, Central Asia and, through the Turkish Straits, to the Eastern Mediterranean and global sea lanes. Each year, more than 40,000 commercial vessels pass through the Bosphorus. Nearly 10,000 of them are tankers. Add bulk carriers carrying Ukrainian, Russian, Romanian and Bulgarian grain; container ships serving Türkiye’s fast-growing industrial exports; and naval vessels operating under the constraints of the Montreux Convention. Few waterways in the world combine such density of trade, such strategic sensitivity and such legal complexity.

Energy Has Moved Offshore – and Into Strategy

The Black Sea is no longer just a transit route for pipelines; it is becoming a production basin in its own right. Türkiye’s Sakarya gas field, with reserves exceeding 700 billion cubic metres, is already supplying the domestic market and is set to expand further. Romania’s Neptun Deep, with around 100bn cubic metres of recoverable gas and production expected from 2027, will be the largest new offshore project in the EU this decade, capable of covering most of Romania’s needs and contributing to regional supply. Bulgaria is integrating into LNG and pipeline networks; Georgia and Ukraine remain transit and storage hubs; and the Caspian–Black Sea corridor continues to offer an alternative route for Central Asian hydrocarbons. Yet the strategic meaning of energy here is no longer only about molecules and contracts. It is about platforms that can be targeted, ports that can be disrupted, pipelines and power cables that can be sabotaged, and insurance premiums that can surge overnight. Drone strikes on tankers, the vulnerability of subsea infrastructure, and the war-risk surcharges imposed on shipping have fused infrastructure security with military security into a single equation.

Food Corridors and Global Stability

The same transformation applies to grain. The Black Sea is one of the world’s most critical food corridors. Ukraine, Russia, Romania and Bulgaria together supply a substantial share of wheat and corn consumed in the Middle East and Africa. Disruptions to exports from Odesa, Chornomorsk or Constanța rapidly translate into price spikes and political stress in Cairo, Tunis, Khartoum and beyond. The suspension and partial restoration of Ukrainian exports demonstrated how maritime insecurity in one sea can reverberate through bread markets and social stability across entire continents. Grain silos, port access, inspection regimes and shipping insurance are no longer merely commercial issues; they are instruments of geopolitical stability. For Africa in particular, where many countries are structurally dependent on Black Sea wheat, maritime security in this basin is a first-order political variable. Food shortages triggered by disruptions in the Black Sea can fuel unrest, migration and state fragility thousands of kilometres away. In this sense, securing the Black Sea’s food corridors is not only a European interest; it is a pillar of global stability.

A Unique Legal Space: Montreux and Beyond

Unlike the South China Sea or the Eastern Mediterranean, the Black Sea operates under a distinctive legal architecture. The Montreux Convention gives Türkiye control over the Straits and regulates the presence of non-littoral navies. This regime has acted as an escalation brake, preventing the basin from becoming a permanent arena of great-power naval confrontation while preserving freedom of navigation for commerce. At the same time, questions of exclusive economic zones, continental shelves, seabed infrastructure protection and freedom of navigation require constant legal and diplomatic management. In the Black Sea, law is not a footnote; it is a core element of deterrence and stability.

Europe–Middle East–Africa: A Two-Way Strategic Artery

What is often overlooked is that the Black Sea is not only Europe’s eastern flank. It is the northern hinge of a much larger system stretching from Northern Europe to the Middle East and, through the Eastern Mediterranean and the Red Sea, to Africa.

Geography works in both directions: Energy, manufactured goods, capital and security flows move southward from Europe through the Turkish Straits to the Eastern Mediterranean, the Levant and the Gulf. At the same time, gas, oil, critical minerals, migrants, data and strategic risks move northward from the Middle East and Africa into the European system. The Black Sea, connected to the Aegean and the Mediterranean by the Bosphorus and Dardanelles, is the narrow gateway through which these continental circulations pass.

In energy terms, the Caspian–Black Sea–Türkiye–Mediterranean axis is becoming one of the few corridors capable of linking European demand with Middle Eastern and Central Asian supply while bypassing choke points dominated by great-power rivals. In security terms, instability in the Levant or the Gulf propagates northward into the Black Sea via migration flows, maritime risk premiums, cyber operations and supply-chain disruptions. The same north–south spine also carries food southwards. Black Sea grain feeds the Middle East and large parts of Africa. When shipping is disrupted in Odesa or Novorossiysk, the consequences are felt in African bread prices within weeks. Thus, maritime stability in the Black Sea directly underpins food security in Africa and social stability across the Middle East. Together, these flows form a three-continent strategic system:

Europe ⇄ Black Sea ⇄ Türkiye ⇄ Eastern Mediterranean ⇄ Middle East ⇄ Red Sea ⇄ Africa.

Energy moves north, food moves south, trade and capital move both ways, and security risks travel in all directions. The Black Sea is no longer a cul-de-sac; it is the central hinge of a Euro-Middle Eastern and Afro-Eurasian geography.

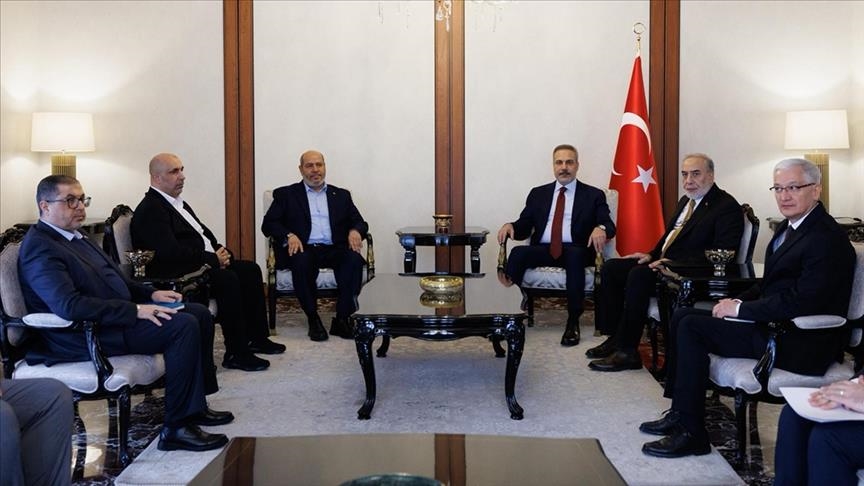

Türkiye’s Centrality

No serious Black Sea security or connectivity equation can be solved without Türkiye. Türkiye has the longest coastline on the Black Sea, controls the Straits, fields NATO’s second-largest military, is emerging as a significant offshore gas producer, and sits at the junction of the Black Sea, the Aegean, the Eastern Mediterranean and the Middle Corridor to Central Asia. It also maintains working – if often difficult – channels with Russia, Ukraine, the Caucasus, Europe, the Middle East and the United States. This gives Ankara a unique role: not only as a frontline ally, but as a strategic convener capable of anchoring deterrence, facilitating dialogue and integrating energy, maritime security and diplomacy across three continents.

For years, the Black Sea was viewed mainly through the lens of NATO’s eastern flank. Today, it also links the southern flank, the Eastern Mediterranean, the Caucasus and Central Asia. European allies are increasing defence spending; Romania and Bulgaria are modernising their navies and air defences; Ukraine and Georgia are central to regional stability; and the United States remains the ultimate strategic guarantor.

Yet institutional responses remain fragmented. Naval posture is discussed separately from energy security; cyber resilience is discussed separately from maritime law; partner support is discussed separately from strategic communications. What is missing is an integrated Black Sea-centred architecture that is:

- Alliance-anchored, with NATO as the backbone of deterrence;

- Legally grounded, fully respecting Montreux and the law of the sea;

- Energy- and infrastructure-aware, treating platforms, ports and cables as strategic assets;

- Hybrid-ready, addressing cyber, information and economic warfare;

- Dialogue-capable, with mechanisms for de-escalation and incident prevention.

The Information Battlefield

Hybrid conflict in the Black Sea is fought not only with drones and missiles, but with narratives. Disinformation about maritime law, energy projects, military intentions and historical claims shapes public opinion and political space. Explaining, clearly and credibly, what Montreux means, what freedom of navigation entails, and why infrastructure protection is a collective interest has become a strategic task in its own right. Strategic communication and public awareness are therefore not “soft” instruments; they are part of deterrence and resilience.

The Next Decade: A Realistic Outlook

Looking ahead to 2035, several trends are likely to define the Black Sea:

- Persistent military competition, constrained by law but shaped by drones, long-range precision strike and undersea systems.

- Rising value of offshore and subsea assets, from gas fields to power and data cables.

- Tighter linkage with the Eastern Mediterranean and the Caspian, creating a single strategic space.

- Greater European responsibility within a transatlantic framework, with the US as the ultimate guarantor.

- Enduring need for escalation control, through legal regimes, confidence-building and communication channels.

The Black Sea now requires more than ad hoc crisis management. It calls for a comprehensive security and stability architecture that integrates deterrence, protection of energy and food corridors, maritime law, partner relations, and strategic communications.

The Black Sea is no longer Europe’s periphery. It is one of the main arenas where the future of European security, Middle Eastern connectivity and African food stability intersect. Whether it becomes a zone of managed stability or a chronic source of systemic risk will depend on whether policy can finally catch up with geography. The strategic hinge is already in place. The question is whether the strategy will follow.